A Learning Model with the Environment in Mind

A learning model that shows how memory and environment work together and reflects how children truly learn in EYFS and Primary.

💡 The Big Idea

Most cognitive science models do a brilliant job explaining how learning happens inside the brain ( working memory, long-term memory, schema, and attention). But they rarely show how learning actually unfolds in real classrooms, especially in Foundation Stage and Primary.

Children (arguably everyone) learn through interaction, movement, tools, and conversation in and with their environment.

So, with a little help from Oliver Caviglioli, I made my own learning model that represents this.

👀 A Closer Look

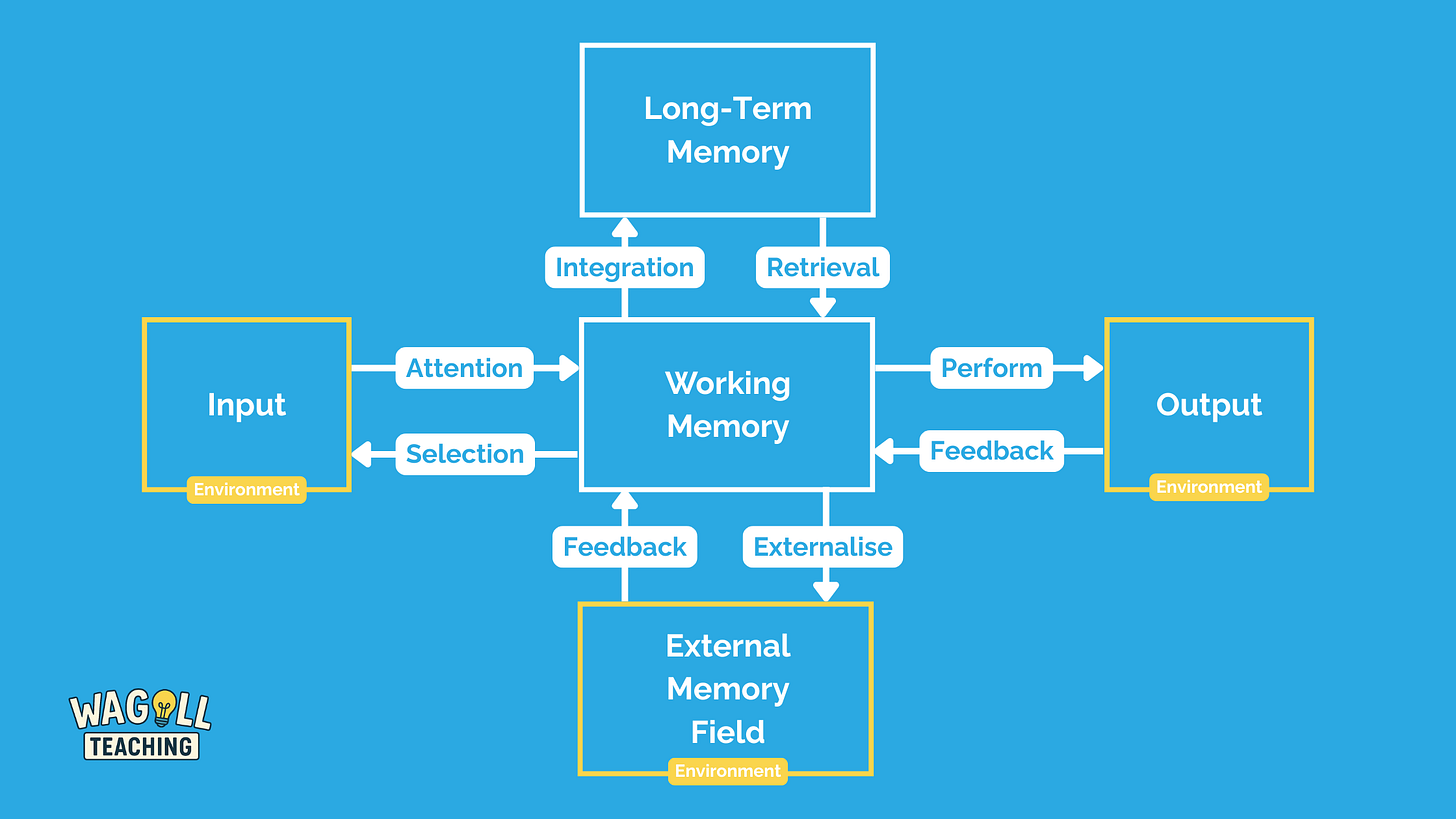

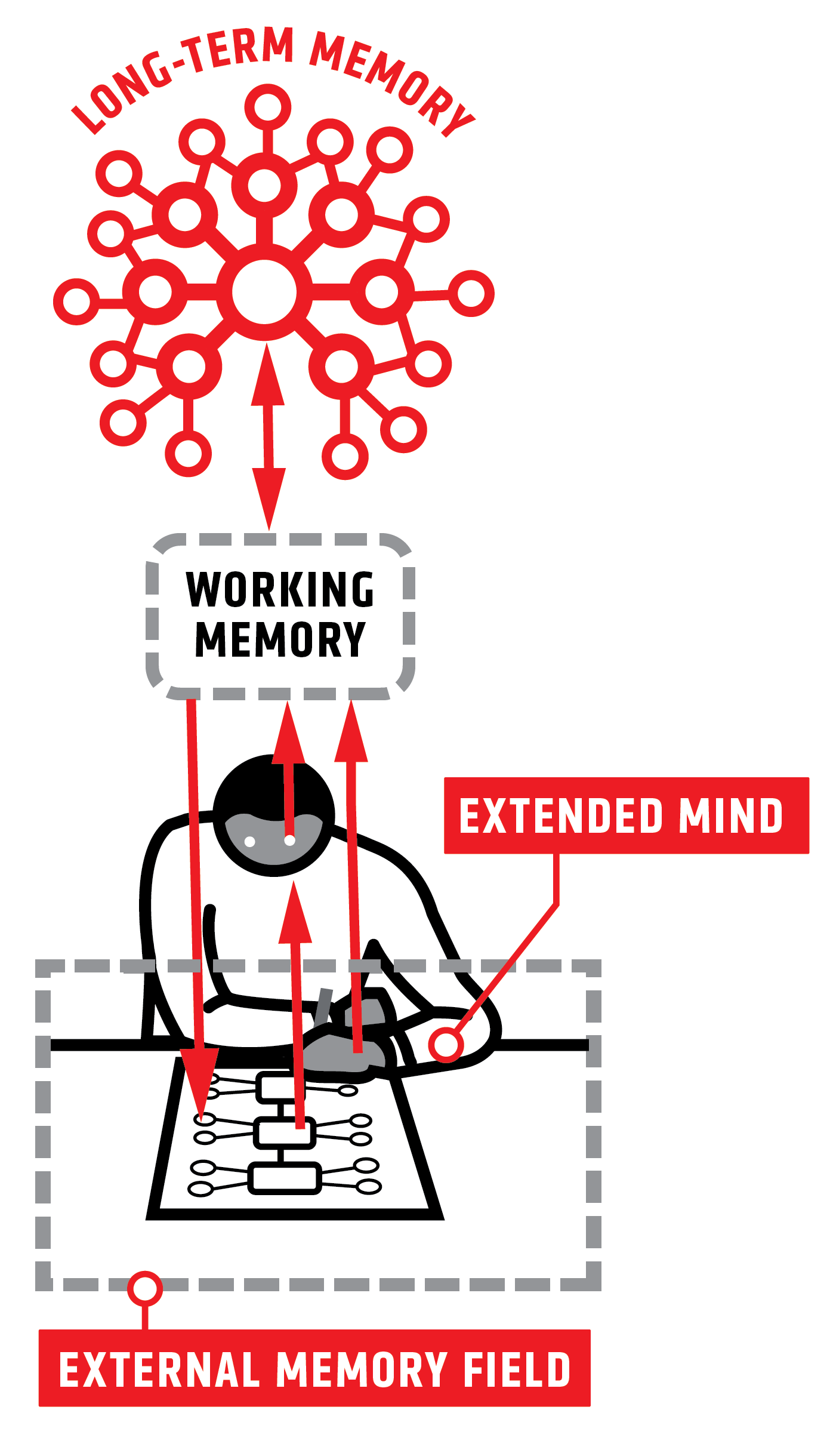

Drawing on Willingham’s work on memory, Fiorella & Mayer’s SOI model, and Caviglioli & Goodwin’s Organise Knowledge, Merlin Donald’s External Memory Field; plus inspiration from The Extended Mind by Annie Murphy Paul, this model blends the internal and the external.

It’s rooted in embodied, situated, and distributed cognition and built for how learning actually takes place in EYFS and Primary.

Most learning models focus on what happens inside the brain and that matters. But in Primary, so much of learning is physical, social, and environmental.

This model is grounded in what Annie Murphy calls embodied, situated, and distributed cognition. In other words:

👐 Embodied – Thinking with hands, voices, gestures, tools

🏞️ Situated – Thinking is influenced by the space around us

🤝 Distributed – Thinking is shared across people, materials, and scaffolds

The Learning Within the Environment Model combines the classic cognitive flow with the process of externalising thinking and learning into the world.

🔁 The Four Feedback Loops

Input ↔ Attention & Selection ↔ Working Memory

Working Memory ↔ Externalise & Feedback ↔ Environment

Working Memory ↔ Integration & Retrieval ↔ Long-Term Memory

Working Memory ↔ Performance & Feedback ↔ Output

Let’s look at each a bit closer.

1. Attention & Selection

Children encounter information Input through teaching, visuals, books, talk, media, and the classroom itself. Sometimes, the environment grabs their attention. Other times, they choose what to focus on.

Teachers can guide this through modelling, gestures, novelty, storytelling, and pausing with purpose. But children also select what to attend to, and knowing how to select is a skill we need to teach too. This is the first feedback loop.

2. Externalise & Feedback

Yes, we know working memory is tiny. In young children, even more so. But it is not all doom and gloom. We can externalise thinking by offloading it into the environment too. It’s the working wall. The whiteboard. The conversation. The partner talk. The role-play. We can use other people’s brains too. Hence, why I always ask my wife if we need anything from the shop. She is far better at holding that information than I am.

Donald calls this the External Memory Field. The environment extends and externalises our working memory, adding far more capacity to what children can process. The External Memory Field is the visual, social, embodied and physical space that can hold our thinking too.

This part of the learning process is so important and places great emphasis on the importance of task design, play and hands-on experiences that enrich a young child’s learning experiences. Not because it is fun, but because it is a key feedback loop to learning.

Indeed, once thinking is more visible and accessible, feedback becomes easier. From peers, teachers, or self-correction, we tweak, refine, and move forward.

3. Integration & Retrieval

I won’t spend too long on schema theory because it is so well written about. But, we know that pupils use Working Memory and the External Memory Field to blend new input with what they already know. This integration builds schema and strengthens understanding. It also works both ways. Retrieval brings prior knowledge into the Working Memory when it is needed.

But, we also retrieve back into the environment through tasks set and through play, conversations and storytelling. A well-designed early years classroom is a jungle of retrieval opportunities to recall vocabulary, concepts, narratives and social habits. The retrieval loop pulls through into the real world, not just our Working Memory.

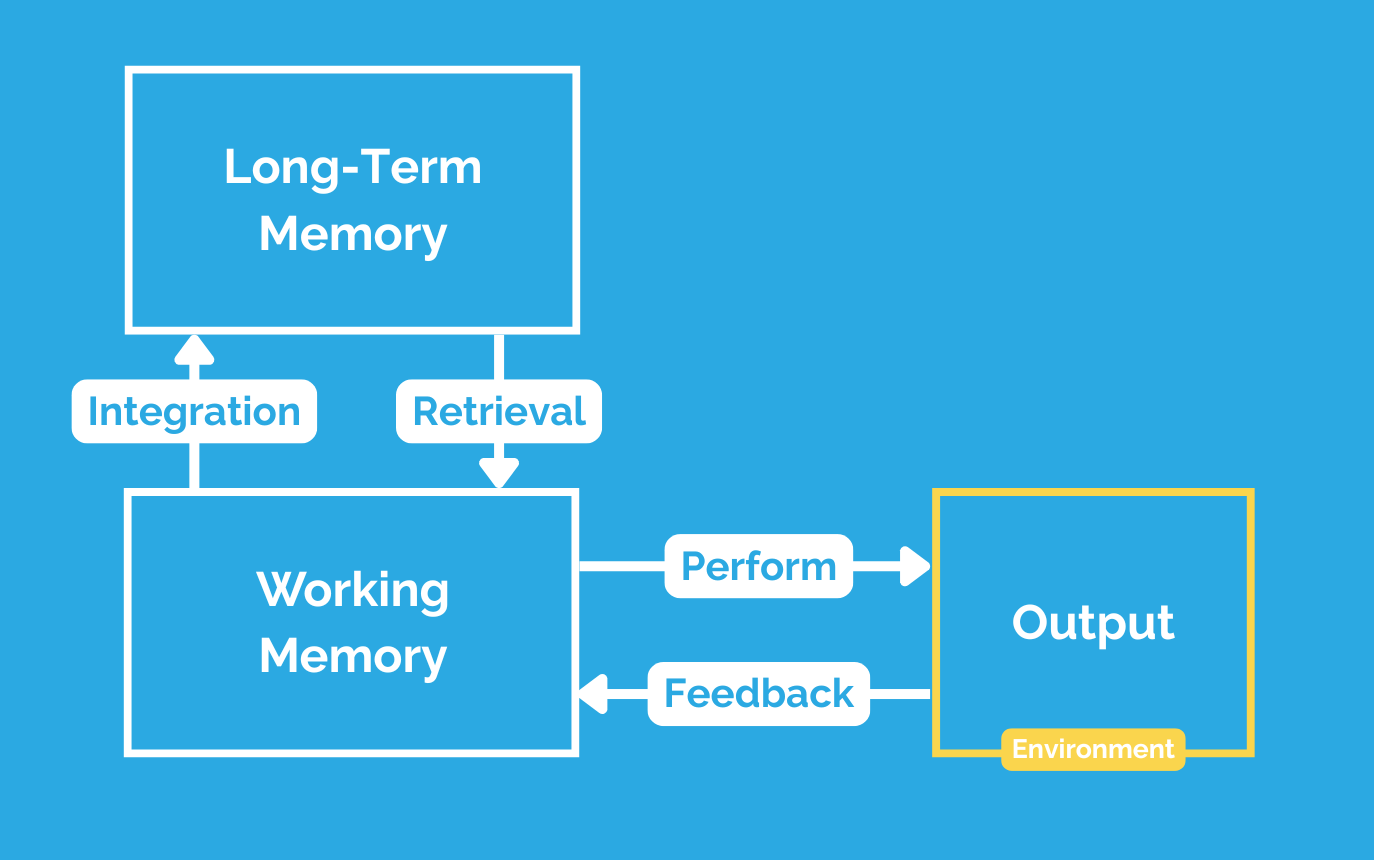

4. Performance & Feedback

I did ask myself the question as to why the Output is different to the External Memory Field? They are both products of thinking. But if the model is to truly represent the learning process, the Output should be different to the use of the External Memory Field. The External Memory Field is the practice. The ‘We Do’ element of learning. The driving lessons. The Output is an outcome. The ‘You Do’. The ‘I bought my own car and I’m driving to the shops’ part.

Earlier, pupils rely on scaffolds and tools to think. That’s the External Memory Field at work. But when scaffolds are removed, and pupils apply knowledge independently, that’s Performance.

Performance is generative. The External Memory Field is no longer a working draft; it becomes a background reference if needed, but is not depended on.

In primary classrooms, this might be writing a story, solving a problem, or retelling a narrative. It might be playing out a restaurant scenario in the role-play area. It’s the moment when children retrieve knowledge and do something with it.

And, just like when we buy our own car and start to drive independently, feedback can still refine our performance, although these habits may be slightly harder to unpick.

🧠 Why This Model Matters in Primary

Tom Sherrington has a great blog on this and outlines the power of an agreed model of learning:

A model helps us understand how learning works and where it breaks down.

‘If the model is any good, it can help to explain things we observe in lessons and help suggest solutions to problems.’

A model can also give us a structure that we can base great lesson and curriculum design on.

Interestingly, Tom also goes on to say that a ‘model could show additional things both as separate and then interacting with memory to add further clarity to our understanding.’

I hope the Learning Within the Environment Model does just that!

In a bit,

Coops 😎

🔓 Want more like this?

This post is part of a growing series unpacking what research-informed practice looks like in a real primary classroom.

WAGOLL+ subscribers get:

✨ Bonus weekly articles and deep dives

📦 Full access to toolkits, CPD packs, and classroom-ready resources

💬 Direct chat — ask questions, request topics, and shape future posts

📝 More from WAGOLL Teaching

The Ultimate List of Books for Research-Informed Teachers ➡️ We’ve pulled together The Ultimate List of Books for Research-Informed Teachers - a handpicked collection of must-reads to boost your practice, challenge your thinking, and keep you at the cutting edge of education.

Exploring Success Criteria - Make Them Dynamic and Accessible ➡️ By presenting success criteria in a more dynamic and relevant medium, meaning can be made, and links can be made to prior learning. Success criteria need to be made domain, subject, and age group specific.

Retrieval Practice: 7 Activities That Work in Primary ➡️ A handy list of retrieval activities for Primary children

📚 References

Caviglioli, O., & Goodwin, D. (2021). Organise Ideas: Thinking by Design. John Catt Educational.

Donald, M. (1991). Origins of the Modern Mind: Three Stages in the Evolution of Culture and Cognition. Harvard University Press.

Fiorella, L., & Mayer, R. E. (2015). Learning as a Generative Activity: Eight Learning Strategies that Promote Understanding. Cambridge University Press.

Paul, A. M. (2021). The Extended Mind: The Power of Thinking Outside the Brain. Mariner Books.

Sherrington, T. (2020, March 10). A model for the learning process and why it helps to have one. Teacherhead. https://teacherhead.com/2020/03/10/a-model-for-the-learning-process-and-why-it-helps-to-have-one/

Willingham, D. T. (2009). Why Don’t Students Like School? Jossey-Bass.